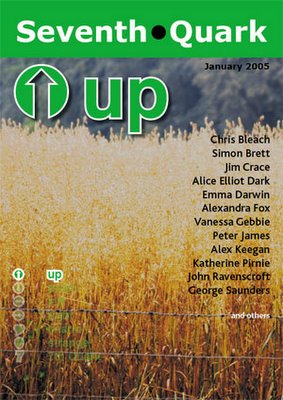

Welcome to 7Q On Line

Issue One was January-February 2005. For a full table of contents, scroll down past the white space I can't get rid of!

While I wait for permissions to republish various stories, here is one from me.

In 7Q we try to publish at least one competition-winning entry from without 7Q. Mother, Questions was a Joint First Prize-Winner in Buzzwords (along with John Ravenscroft's Watch With Mother and an article by Buzzwords Editor Zoe King.

Such comparisons and editorial commentary are typical of what we aim for in 7Q.

To entertain, yes, but to teach at the same time.

MOTHER, QUESTIONS (Seventh Quark, Issue 1)

Mother, can I ask, with you and Dad, my father, how did it happen, how was it? Were you frightened, excited? Was he strong, was he clumsy?

You told me once, before you died, you said, "We walked out for almost a year and then, one day, on a bridge over the canal, he asked if he could kiss me." You said you laughed, couldn't help it. He ran home.

So Mum, how did you get from there to being my mother? How did that shy young man learn to make love? Was he your first, Mum? Nellie said to me once, (she was drunk on gins), she said you had a beau everyone wanted, but he was "a bit of a lad, a heart-breaker", wouldn't take no for an answer.

I always wondered, wondered how I happened. I'm here, some kind of me, and I'm you, the bridge across the water, my hopeless father. Am I my sisters too, am I my brother? If they hadn't come before me, you would have been different, things would have been different, nothing, nothing, nothing would have happened exactly as it did. I wouldn't be this me, I wouldn't be able to ask these questions. How can it be that I exist without it being necessary that I exist? But how could these loves, bridges, kisses, how could they have all made my history, made me this, put me here?

You said once, you said Bill and Nellie were going to get married. You said you were on a tram going up Cambrian Road. You were opposite sides of the aisle and Dad shouted across at you, "We could make it a double wedding!" You told me that you laughed. You told me you said yes, but you didn't know why. Mum you could have said no.

I remember you talking about the trams, the way they were always full, the way they clanged. You said they were big and solid and real. Your eyes were always alight when you talked like that, I loved that look, but it wasn't there when you talked about saying yes to Dad. On the day of the wedding, on the day of the wedding, you wanted to be anywhere on earth rather than St Mary's. You said that. Mum, how did it happen? How could you have let it happen?

My memories of you don't come in a line, Mum. They're like flashes of sunlight through trees, but I'm on a train going in circles, I'll maybe get to come round and see again. I have your photograph, the one from the war when you were in your ATS uniform and still had puppy fat, but I could see the woman in you, the deep heat men seek but can never understand.

It's black and white - well, brown, more like, and you and the other two girls, all that life-power, and yet the three of you look so soft, so quiet, just waiting. Did all women wait then, Mum? Did they just contain? I don't know how else to say it - you know I missed a lot of school - I don't always find the best word… But contain feels right … but I can look at your picture and see you with history waiting in your belly. I can look at that picture and I can see my life, all of it, see your grandchildren, your great-grandchild (Pat's Jackie had a baby boy - pretty little thing), I can see everything, all the good things, everything.

Now you know what life is Mum, was it all to come, was it pre-set, was it laid out, was it a book and we just flicked pages? Does he talk about it as if it was all so obvious, what else could have happened, does he, do they? What is it Mum, I mean what's there, I mean do you now think it was all a landscape and we just felt our way forward, we weren't doing anything? Does that excuse the things we do, things you did, Dad did?

They probably knew about DNA when you were still alive Mum but we didn't talk about it. Now we do, we talk about it, about inevitabilities, about tendencies, predispositions. Some people say there's no free will, not really, even choosing or not choosing is wired into us. That's what I mean when I say contains, it's all in the belly, it was all there in your picture, you, and I guess my father, his father, your father, mothers and fathers, all the way back as far as we can imagine. Someone made my father my father, he didn't. Someone made you, you didn't. You could have said no, but you didn't. That was wired in too, I guess.

I wish sometimes I could get at my DNA. That would be something, eh, Mam? I could go in there and tinker. I could give myself cancer or make myself big enough to fight. Imagine I could have done that when I was ten, before you left us and ran away to London? Imagine if I'd been big and strong.

They tell me what happens, happens and it's not our fault, but that how we are made, that makes a difference. It's whether we're built to withstand things or whether we are soft. I guess they'd say I was soft, but Mum, when you say something, people should believe what you say, not decide your DNA has some wrong bits, not decide to rush volts into you while you bite a piece of wood, make you eat pills until you're someone else.

I know you ended up here once, Mum. They said you had a nervous break-down, didn't they? They said you lost your purse and couldn't cope, that you started crying on the number three bus and they stopped the bus and rang for an ambulance. But you just rested here a bit, didn't you? Got away from the house for a while, from Dad. And I know what really happened to the money. I don't blame you, Mum. Dad used to bet on the horses.

They brought me here the first time when I was thirteen, Mum, thirteen. Now I'm forty-eight and how far have I got, just round and round on that train, looking for the light through the trees. I was here three years, meat, and they took away someone from inside me. When I looked in the mirror I was old, old as a child, Mum, grey and sick with sores round my mouth.

And it's all to do with you, Mum, my mother, and Dad, my father, and DNA, and fathers and mothers and monsters, way back to when there were caves and we made things out of stones. Mum, have you ever thought, all those deaths in childhood, diseases, wars, tribal sacrifices, fires, people falling into pits, and yet my father, his father, his father and fathers, fathers, fathers, not one died before he made a child. Here I am, forty-eight a mother and a child and I connect to when we were worms. It's amazing, Mum.

Pictures are funny things, Mum. If you look at them they move, they swell up and then they go back again. People in the jungle say pictures contain the soul. Oh, I've said contain again. There's a picture contains your soul, your you, and your you contains everything, including me, and my little Jenny, she would be in a picture of me, in my belly, in our histories.

You would have liked Jenny, Mum. She's dark like you, has the Irish in her, the light. How, I'm not sure, but I think it's real enough. I read once that genes only pretend to divide themselves up, that sometimes they leap about in packs. If that's true I can understand it. Mum, sometimes I think my Jenny is you.

Here, when they go on at me, one of the things they talk about is circles, things going round, things repeating, me saying the same thing. Were they like that with you, Mum or did they just know you were resting? They go on at me as if circles are bad things, as if me noticing the way things come back round is bad, but I don't see it, Mum, I really don't. We are mothers and daughters, that's a circle, and we're pictures, and we contain, don't we? You were a picture, I was a picture. Then Dad came along for you, and Jimmy, Pat, Sharon, me, we all happened, it's all circles; then I found myself a mother and back there again, round and round and round.

But why do they think I'm a liar, Mum? Why do they think way back then, when I was still just twelve, I was a liar, why now do they think I'm a liar? Did they think you were a liar when you said you'd lost your purse? Did it matter? You needed a break, so you started crying and wouldn't stop, and they pulled the bus over, called an ambulance, took you away for a rest. Nobody said, "Stop crying, you liar! We don't believe you, pull yourself together!"

Mum, I guess you know now. I never lied.

I remember something. the Lido. I remember your fat shoulders covered in freckles, the easy blubbery way you swam.

I didn't want to go in the big pool but Dad laughed, grabbed me, and took me in. It was cold and there were leaves in the water, twigs. Someone had burst open a packet of crisps and they floated on the water. At first I held on the side of the pool. You were in a good mood, it was a sunny day, and you said something and swam away. That was when Dad pulled my hands from the edge and took me out into the middle. I cried and he said if I didn't shut up, he'd drown me. You swam back. You said something and then Dad let me off. I went in the kids' pool with the others.

You were such a good swimmer, Mum. I only ever remember you as big and brown, solid and safe. You looked like a whale, a ship, a raft. Like when you said the trams were huge and warm for you, well that was how it was with me and you. Nothing is solid now Mum, nothing has been big and safe, not since just before I was thirteen.

I know you had to go Mum, you had to run away. I don't know exactly why, but I do understand. I understood. Even then I could feel things, know things, see circles of life. I knew you were spiralling down, down and something had to happen. I don't mean I could say that, then or that I can tell you now what exactly I knew. But I knew.

When they go on at me here, they tell me this kind of knowing isn't a proper kind of knowing and that's why I'm here, but it's easy for them, they have their trams, their fat mothers, churches, mountains, they aren't like I am. They have to be here to know. I don't mean just here, I mean here, where I am head-wise, in my sad shoes - well slippers, they won't allow shoes. They were never thirteen, taken to the room, sent black in a second. They never woke tasting wood and blood with the world in a cupboard.

It was just before bonfire night when you suddenly weren't there. One of the flashes is Barbara and me, coming down Gaer Hill and she's telling me and I wouldn't believe her. Dad cut himself shaving and hit Pat. We had burned toast with the black scraped into the sink where dad's blood was.

Porridge and burned toast. We had porridge as well, Quaker Oats. You did porridge usually, soaked the oats overnight, let them get fat and soft. I remember fat and soft. You, I think of fatness and softness and roundness and you big in the pool, swimming away, then coming back to rescue me with a light laugh.

When dad was on six till twos he'd do some overs, come back through the park at Mendalglief. We'd run down when we saw him coming. If they made a film of dad now they'd show him coming up through the trees (the monkey-steps short-cut) dark with oil and steel, a dirty paperback under his arm. It would be sunny, there'd be Hovis music playing and we'd rush to him, he'd pick one of us up. His smell! He was darkness, tobacco, the steel, and some man-thing men don't smell of now. Pick me up, fly me, Dad.

On six-'till-two.

On ten-'till-sixes, the housenight was colder, echoey, but we just got used to it. Kids can get used to a lot, Mum, you'd be surprised. They didn't take us away because Pat was old enough to do stuff and I was able to help with bits and pieces, but then she went too, off to London to be with you. But the ten-to-sixes were OK.

When dad worked two-till-tens he never worked overs because he wanted to go up the Plough before they closed. He used to go to the Plough, have a few Ansells before coming home. Sometimes he'd bring us all chips.

I think of you Mum, when I think like this, I think of you, how you were big and brown, a house, a tree, a river, safety. I want to be with you, why can't they understand that.

2,287 words.

Previously published in Buzzwords

SCROLL (way down) for Table of Contents)

| From Seventh Quark | 7Q |

| Finding the Story | Alex Keegan |

| How to Leave Iraq | George Saunders |

| Maura's Arm | Emma Darwin |

| Annie, California Plates | Jim Crace |

| Letters | 7Q |

| Like it Was | Vanessa Gebbie |

| Heirs to Munch | David Prescott |

| Punctuation; a Lexicon circa 1999 | Gina Ochsner |

| Picture Me Resplendent | 7Q |

| The Falls | George Saunders |

| Another Day in Paradise | Mark Watkins |

| Watch With Mother | John Ravenscroft |

| Mother, Questions | Alex Keegan |

| The "Mother" Question | Zoe King |

| Why They're Not Talking to Me | Cedric Popa |

| How to Write Sex Scenes | Steve Almond |

| Gethseminal | Alexandra Fox |

| The Carpenter's Wife | Katherine Pirnie |

| Pictures at An Unattended Exhibition | Martin Roxby |

| Dead Simple | Peter James |

| Green & White | Chris Bleach |

| Young Writers Section | Nicky Singer |

| Embodiments | Alice Elliott Dark |

| Angel | Bridie Peejay |

| STUFF | 7Q |

| Hair Manners | Nancy Saunders |

| Sensitive New Age Cripple | Glenn Fowler |

| Cheese Penis | 7Q |

| Inside the Back Page | "Mary Trafford" |

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home